A framework for multipurpose content development

PaperMichela Negrini, italy , Paolo Paolini, Italy

1. Background and position statement

In recent years, the possibilities of deploying Cultural Heritage content have been greatly enhanced, since a large varieties of channels are available: “traditional” Web, Web for mobile devices, apps for mobile devices, audio guides, multimedia guides, YouTube, Facebook, other video channels, large displays, multi-touch tables, podcasts, virtual visits, phone calls, etc. The various channels serve different purposes: providing practical info, allowing would-be visitors to prepare their visits, supporting visitors during their visits, allowing past visitors to further explore content, allowing some kind of virtual visits, supporting “learning activities” for students and teachers, supporting research activities by scholars, etc. It is often the case that a cultural institution facing a new delivery channel or supporting a new purpose will create new content rather than reusing existing content (possibly after some kind of adaptation; for example, www.nipponlugano.ch; www.giorgiomorandilugano.ch).

There are several reasons for such apparently surprising behavior:

- Technical motivations: each device/technology may require different technical formatting, different interfaces, different interaction paradigms.

- Organization motivations: different channels/devices are often taken care of by different teams. Thus, it is often the case that the Web, the multimedia guide, the podcasts, and the audio guide are all different.

- Communication motivations: changing devices and technology often corresponds to different situations of usage. A visitor standing in front of an exhibit needs a different kind of communication with respect to a user sitting at home and looking at a Web page.

The above situation has some unpleasant consequences for the user who by now is often “multi-channel”; that is, using (at different times) a PC, a smartphone, an interactive installation, the multimedia guide of the museum, YouTube, podcasts, etc. The user is often getting uncoordinated content (with minor or major differences among the various channels) without understandable reasons. Negative consequences surface also for the institutions, including duplication of efforts, length of time for deployment, costs. This is especially negative for small institutions that cannot afford to start a new content effort every time a new technology or a new device must be used.

Given the above considerations, for a number of years HOC-LAB and TEC-LAB have attempted to improve the situation (e.g., www.nipponlugano.ch; www.giorgiomorandilugano.ch) and make the deployment of content over various channels more consistent, less expensive, and more effective. In this paper, we present a full-fledged framework, 1001stories+, for facing the various issues related to delivering high-quality content over various technologies and devices, serving various purposes and various situations of usage. The framework consists of three overall components:

- An overall workflow, suggesting how to organize and manage the various steps for content production

- A methodology for adapting content to various needs and various devices

- An authoring/delivery environment that can be used by non-technical content editors to generate high-quality content

In section 2, we illustrate some real-life case studies. In section 3, we describe the framework. In section 4, we draw conclusions and present our future work.

2. “Giorgio Morandi Multimedia”: An example of content adaptation

In this chapter, we present a case study in which the 1001stories+ framework was largely adopted: the occasion was an exhibition on the Italian artist Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964), held at Museo d’Arte, Lugano, from March to July 2012. One of the most distinguished and yet most enigmatic artists of the twentieth century, Morandi is renowned for his meticulous artistic research as well as the process of deep investigation he carried along his entire life. This exhibition, throughout a corpus of approximately one hundred works, traces a line along the most significant moments of his production. For this emblematic exhibition, a multimedia component was created, including three different “narratives”:

- One on the general themes of the exhibition (figure 2a)

- One with the main techniques used by the artist along his career (figure 2b)

- One on a selection of artworks (figure 3)

Each “narrative” consists of a set of content elements: videos (audios plus a slideshow of images) with text visible on demand. Each content item lasts between one and two minutes at most, to fit the time preferences of the typical “digital user.” As far as the content is concerned, the multimedia section dedicated to the general themes provides further tools to non-expert visitors in approaching the exhibition itself. The thematic narrative is organized as a sequence of six pieces of content (an introduction and five themes), each about a specific topic (figure 2a). The section “Techniques” is organized as a sequence of five pieces: an introduction to the techniques used the most by the artist, and the four techniques themselves (figure 2b). The third multimedia section is “Selected works/Highlights” (figure 3), dedicated to a number of exhibited works.

The whole work was developed exploiting the 1001stories+ workflow. First of all, preliminary research on the topics of the exhibition was conducted, and interviews with the exhibitions’ curators were held. Then, the multimedia content was created and edited: the texts, the visual communication, and the professional recording of the verbal content. Then, all the multimedia content (texts, images and audio files) were introduced into the 1001stories authoring environment to generate the desired versions: “traditional” Web for PC (interactive), a YouTube video (with a linear, non-interactive sequence of elements), and an on-site guide (again linear, but including instructions on how to move from one work to the next). The whole work is available over several devices: PC, mobile devices, smartphones, etc. The authoring environment and the production workflow have been widely discussed elsewhere (Paolini et al. (2011); Di Blas et al. (2007); Paolini & Di Blas (2014)). Let us now focus on the content adaptation procedure.

The multimedia content created for the exhibition can be easily adapted for a number of delivery platforms to address the available technologies and devices, serving various purposes and various situations of usage. Three different versions of the same communication were envisioned:

- Interactive on the wWb (e.g., users access the online material when preparing for the visit, or after a visit, for curiosity)

- Linear (e.g., users may access the multimedia content on YouTube)

- Guide on site: users may look for additional content, such as physical instructions, while visiting the exhibition

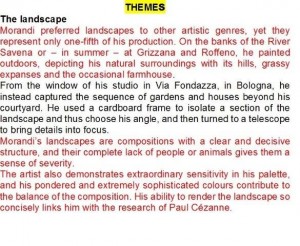

For the Giorgio Morandi exhibition, the multimedia content was created once and for all, and thanks to small adaptations, it was reused to fit the above needs. Each content element can be dismembered and recombined to serve different deliveries and purposes. Let us see an example (figure 4): a content element from the “Themes” narrative (here in text only for practical reasons) is dismembered, obtaining different and self-standing content items, ready to be reconstructed and repurposed.

Figure 4 shows the multimedia content of item “Landscape.” The text is being analyzed and dismembered into four parts. The text in RED shows the different text items (three in this case) that will be recombined, forming new adapted items. In order to generate the YouTube (linear) video, each fragment from the selected element is recombined with an item from the “Selected work” narrative, forming a new piece of content, as shown in figures 6 and 7. In order to generate the on-site guide, the same process is undertaken, but adding new content: instructions on how to move from one work of art to the next. As the reader can see, the same content travels across the different delivery channels, and only a few adjustments and very simple new content needs to be added.

Summing up: the Web content is organized into themes, techniques, and selected works, whereas the YouTube (linear) version and the guide-on-site version present a combination of bits of the general theme and the artwork together, allowing the user/visitor to acquire pieces of information little by little, gaining a complete overview by the end of the content fruition. This case-study example illustrates how, starting from the same content, in a multimedia environment, the same items can give rise to different versions, in a cost-effective way. Let us now formalize the process:

- Interactive version on the Web (figure 5)

- Narrative about themes: T1, T2 …Tn

- Narrative about selected works: W1, W2…Wm

- Interactive links: T1à {W2 , W4}, T2à {W6 , …W12},

The thematic (T) and selected works (W) narratives are organized as sequences of content. The first are about a specific topic, whereas the second are dedicated to a number of exhibited works. The interactive links allows users to move from themes to selected works (figure 5). Different works share the same thematic item, and therefore are linked to the same theme, providing the user with an interactive exploration and a deeper understanding of the artist’s work.

- Linear version (YouTube): content about themes is distributed (figure 6)

- T1: F1+F2+F3

- The theme T1 consists of three “fragments”

- The linear version (e.g., YouTube) is: <F1.W1, F2.W2,….>

The thematic narrative (T) consists of a number of fragments (F), as shown in the above (text-only) example (figure 4). When a linear version is created, the thematic content is fragmented and distributed across the number of selected works (W), resulting in a combination of bits from the general theme and the artwork.

- A guide on site (figure 7)

- Additional content items for physical instructions

- G1, G2, G3

- <F1.W1.G1, F2.W2.G2, …>

The guide on site could be considered a sort of evolution of the linear version with additional instructions (G) on how to move in the exhibition space.

Figure 5: Giorgio Morandi Multimedia, the Web version supports interaction: the user can move from themes to selected works (links on the right-hand side)

This example shows that by creating multimedia content once, and with simple adaptation efforts, proper reuse allows a number of different and original multimedia productions, providing substantial benefits:

- “Horizontally,” at a certain time:

Authoring is intrinsically expensive, since knowledgeable people are involved to convey information and emotions to users. It is therefore important to maximize the outcome:

- Supporting a variety of devices

- Supporting a variety of user experiences and profiles

- Supporting a variety of contexts of usage

- All of the above combining quality with low costs and short development time.

“Vertically,” over time:

- Multimedia content, developed for a specific event, is “locked” in the audio-guides or multimedia guides and thrown away when the event is over, or “archived,” becoming practically invisible, not to be used anymore. It would be desirable for each institution to reuse its content over time, repurposing it for different situations (a different exhibition, a catalogue, etc…).

3. The framework: 1001stories+

In this section we illustrate the 1001stories+ framework: an authoring/delivery environment, a combination of methodologies for adapting content, and an overall workflow. As was said in the previous section, the goal is to be able to quickly (and easily) move the content across different devices, different situations of usage, different information architectures, and different interaction styles. Moving content around, as it was argued before, can not be just a mechanical job; in most situations some kind of “adaptation” is necessary. The aim is to keep this adaptation as simple as possible, in order to save effort, time, resources, and therefore costs. 1001stories+ is an offspring/evolution of the authoring environment 1001stories, which has been described already in several publications (Paolini et al. (2011); Di Blas et al. (2007); Paolini & Di Blas (2014)). With respect to that ancestor, this innovative framework represents an evolution in several respects:

- The authoring environment is much more powerful and flexible

- The generation/delivery engine has become more general and tunable (in order to fit various deployment needs

- Content-production methodologies have been better defined

- The overall production workflow has been identified and standardized

We will now examine, one by one, the components of the framework.

A. The authoring environment

The new version of the authoring environment allows a sophisticated production of small multimedia “items.” An item can be made of one or more “fragments.” Individual fragments can’t be played on their own: only items can be played. An ordinary fragment has a “read component,” a “visual component,” and an “audio component.” The read component is textual (with no specific formatting required). The visual component can be implemented in several ways: a sequence of images (e.g., pictures or slides) or an ordinary video or an animation. The audio component consists of an ordinary audio. An item consisting if several fragments (in a given order) and stitches together the various components of the constituents fragments. The above arrangement may become more complex since some fragments may have a component missing. For example, the first fragment has three pictures, the second fragment has a “silent video,” and there is a unique audio track spanning over the two fragments. A set of rules defines the “length” of an item when it is played.

Advanced features

There are special fragments, generically labelled “pre” or “post.” A fragment “pre” can be stitched only before all the other fragments, while a “post” can be stitched only at the end. There are several uses for these special fragments: they can be used to provide context information (e.g., the name of the museum) or practical info (e.g., “in order to reach next stop you have to…”). These fragments are a key aspect of content adaptation and can be “tagged.” During the generation phase (see below), only the fragments with a given tag will be used, and in the specified order. Items are combined into “narratives.” Presently, we have two types of formats (with two more already “designed”):

- Flat: basically a playlist of items

- Tree: items are arranged in a hierarchical fashion (two levels). The top level represents the “short version” of the narrative, while for each item of the top level a sub-tree provides details.

A format corresponds at the same time to an information architecture and to a way to play it. Consider, for example, a catalogue with twenty works. We would probably associate to it a flat narrative, which is a playlist. This playlist can be played in a number of ways: sequentially (following the exhibition), randomly (in correspondence to a number displayed on the side of the work), automatically (e.g., by position detection), etc.

Narratives can be grouped in a “cluster.” The exhibition about Morandi, for example, included four narratives: “themes,” “techniques,” “catalogue,” and “virtual visits.” Items can be linked to other items of narratives belonging to the same cluster. For the exhibition of Morandi, for example, items of “themes” are linked to items representing individual works (that belong to the narrative “catalogue”). Items can be also linked to “external resources”: files that can be played, PDF files, URLs, and alike. Narratives therefore can be used to access a host of external information.

B. The generation/delivery environment

During the “generation phase,” a “content editor” decides which narratives must be generated and selects the proper “generation parameters.” The parameterization may include the identification of the device(s), whether the selection of the media should be included, if the indication of tagged fragments must be included or not, or if linked items must be included or not, etc. The output of the generation phase is a “generation database,” where the items are stored (processing the various fragments) only including the needed media and with the suitable organization. After the generation, there is a “delivery process” that makes the final results available (e.g., a website, a playlist, podcasts, an interactive app, videos for YouTube, etc.). The separation between “generation” and “delivery” may seem useless, but it is crucial for saving costs and time. Generation corresponds to an editorial choice, while the deployment depends more on technology. Therefore the generation process has some intrinsic complexity (e.g., properly combining the media of various fragments) while the deployment has only strictly technical problems.

This solution has several advantages. Just to mention a few: whenever a new technology appears, we only need to add a new driver for deployment (which is relatively simple), and we do not need to modify the generation process (which is cumbersome and expensive). In other words, we can easily adapt our narratives to a new technology, not foreseen when the narrative was created.

C. Production Methodologies

A key point of the framework is the identification of a suitable production methodology that allows us to keep down costs and time to delivery, at the same time ensuring a good balance with quality. The fundamental rules are the following:

- Very early, the “story” to be told is broken in a number of items

- Each item is developed almost independently from the others; sometimes different people work at the different items, with a parallel production process

- For each item, the “visual” component is developed independently form the other components

- By far, we prefer the “generation” of video from images and pictures, rather than editing real video, which more time consuming

- The visual components are assembled with the textual components and tested with a “homemade” audio track (using nonprofessional speakers)

- When the final version of the textual components is available, professional audio (with professional speakers) is recorded.

- Once everything is assembled, the visual components are revised and still improved in order to better match the audio

The production flow depicted above ensures that, in a relatively short period, we can deliver complex stories. At the same time, we can work in parallel on several stories.

D. Overall workflow

Once the backbone of a story is created, it is often “morphed” into several versions: for standard delivery on the Web, for smartphone, for a virtual visit, for a visit on site, for a YouTube channel, for a “paper” version, etc. Sometimes these various incarnations require some degree of content adaptation, in the sense previously described in this section. In most cases, content is added rather than modified. Assume, for example, that a “catalogue” is created for the Web, with a short story for each exhibit; if we wish to obtain an “on-site guide,” the following could be the steps:

- The works are rearranged in the proper order for a visit

- Pre-post fragments are created in order to support the visit; that is, before moving to next exhibit (or after the current exhibit), the visitor is given proper instructions about how to move around

- A proper “introduction item” is created (for introducing the visit), and a “closure item” as well (for a farewell to the visitor)

One working day is our estimation for the complete effort necessary to transform the Web catalogue into a guide that can be delivered as a Web application or an interactive APP. The overall workflow is agile and flexible, making it possible to quickly react to new usage needs or to modify the delivery technology.

4. Conclusions and future work

The framework presented in this paper, 100stories+, was developed as result of various applications developments. As of May 2014, the authoring/delivery environment is being totally revised, with a full deployment foreseen for July 2014. The framework will be made available (free of charge) to cultural institutions worldwide. Our current test beds are the following:

- “Sala delle asse” (http://www.saladelleassecastello.it/?lang=en): an effort in cooperation with the City of Milan, to interpret the restoration of a room in the “Castello Sforzesco” that was painted by Leonardo da Vinci (either directly or with his workshop).

- “Lugano Mobile”: an experimental effort to improve communications at the various museums of the city of Lugano (in Switzerland) in view of the opening of the new LAC building, planned for the end of 2014. As of the beginning of this project, the Cantonale museum, Museum of Art, and Museum of the Cultures are involved.

- “Policultura Expo Milan 2015” (http://www.policulturaexpo.it/http://www.policulturainternational.net/): an effort to support content production by schools for EXPO2015 http://www.expo2015.org/en/index.html), the large fair that will open in May 2015 and is expecting twenty million visitors.

In addition, experimental uses of the framework are being discussed with other major cultural institutions in Italy.

Acknowledgements

The authors warmly thank all the people in their labs: HOC-LAB (Milan) and TEC-Lab (Lugano).

References

Campione, P., N. Di Blas, M. Franciolli, M. Negrini, & P. Paolini. (2011). “A ‘Smart’ Authoring and Delivery tool for Multichannel Communication.” In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums And The Web 2011 Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Available http://conference.archimuse.com/mw2011/papers/smart_authoring_delivery_tool_multichannel

Caporusso, D., N. Di Blas, & P. Franzosi. (2007). “A Family of Solutions for a Small Museum: The Case of the Archaeological Museum in Milan.” In D. Bearman and J. Trant (eds.). Museums and the Web 2007. Selected Papers from an International Conference, Archives & Museum Informatics, San Francisco, California, USA.

Di Blas, N., D. Bolchini, & P. Paolini. (2007). “Instant Multimedia: A New Challenge for Cultural Heritage.” In D. Bearman and J. Trant (eds.). Museums and the Web 2007. Selected Papers from an International Conference, Archives & Museum Informatics, San Francisco, California, USA.

Di Blas, N., E. Rubegni, & P. Paolini. (2008). “Enigma Helvetia, Promoting an Exhibition through Multiple Channels.” In Proceedings of the Information Access to Cultural Heritage (IACH) workshop, organised in conjunction with the 12th European Conference On Research And Advanced Technology For Digital Libraries (ECDL 2008), September 18, 2008, Aarhus, Denmark.

Paolini, P., & N. Di Blas. (2014). “Storytelling for cultural heritage.” In A. Contin, P. Paolini, and R. Salerno (eds.). Innovative Technologies in Urban Mapping (33-48). Springer, Series: SxI – Springer for Innovation.

Rizzo, I., & A. Mignosa. (eds.). (2013). Handbook on the economics of cultural heritage, Elgar, Cheltenham.

Rubegni, E., N. Di Blas, P. Paolini, & A. Sabiescu. (2010). A format to design narrative multimedia applications for cultural heritage communication. In Proceedings of the 2010 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing (SAC ’10). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 1238-1239.

Links to Web Resources

- HOC-LAB: hoc.elet.polimi.it. The website of the laboratory based in Milan. In the “digital storytelling” section, a number of examples of multimedia narratives can be found.

- TEC-LAB (Technology Enhanced Communication Laboratory, www.tec-lab.ch) is a research lab at the Faculty of Communication Sciences of USI, the Università della Svizzera italiana (Switzerland), which develops theoretical and applied research to establish in what way the use of technologies and interactive media can back up and reinforce communication processes, in particular in the area of cultural heritage and e-tourism.

- Giorgio Morandi (www.giorgiomorandilugano.ch). Throughout a corpus of approximately one hundred works, the exhibition traces a line along the most significant moments of Morandi’s production. Done in 2012, in cooperation with TEC-Lab, for the Museo d’Arte, Lugano, Switzerland.

Cite as:

M. Negrini and P. Paolini, A framework for multipurpose content development. In Museums and the Web 2013, N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds). Silver Spring, MD: Museums and the Web. Published June 16, 2014. Consulted .

https://mwf2014.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/a-framework-for-multipurpose-content-development/